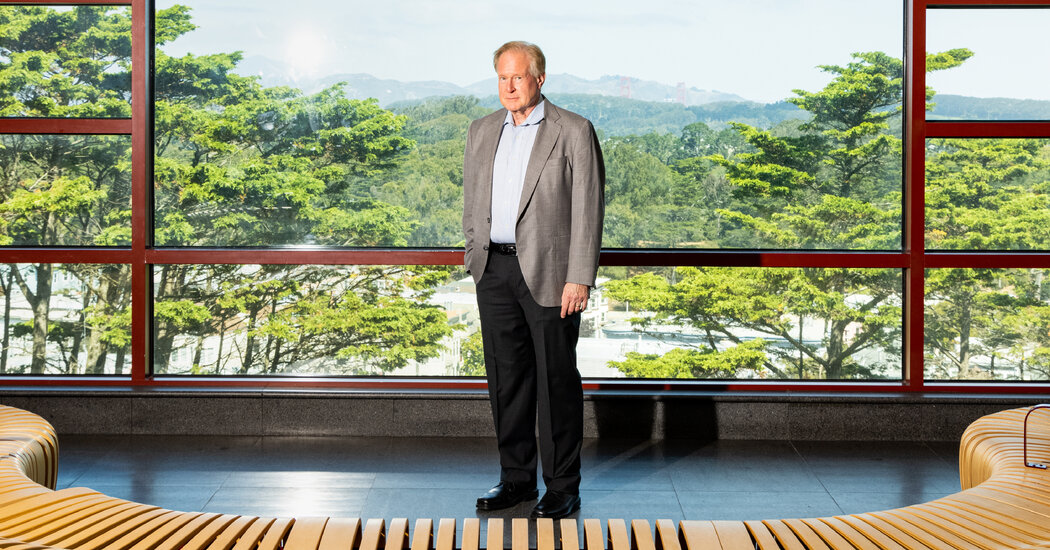

Dr. Robert H. Lustig is an endocrinologist, emeritus professor of pediatrics at the University of California, in San Francisco and author of Best Selling Books On Obesity.

It is absolutely not – despite what you could see and listen to on Facebook – “liquid pearls” foul with dubious statements on weight loss. “No injection, no surgery, only results”, seems to say in a post.

Instead, someone has used artificial intelligence to make a video that imitates him and his voice, all without his knowledge, let alone consent.

The posts are part of a global wave of frauds who divert the online people of important medical professionals to sell unreserved health products or simply to make up the Creduloni customers, according to the doctors, the government officials and the researchers who have monitored the problem.

While health care has long been attracted to the tackery, the artificial intelligence tools developed by Big Tech are allowing people behind these imitations to achieve millions online and profit from it. The result is the disinformation of sowing, undermining trust in the profession and potentially endangering patients.

Although the products are not dangerous, the sale of unnecessary supplements can arouse false hopes among the people who should receive the medical treatments they need.

“There are so many wrong things in this,” said Dr. Lustig – the real one – in an interview when he contacted imitations. The interview was the first time he learned.

The Food and Drug Administration and other government agencies, as well as defense groups and private guard dogs, have intensified the warnings on counterfeit or fraudulent health products online, but they seem to have made little to stem the tide.

The progress of artificial intelligence tools have made it easier to generate convincing content and spread them on social media platforms and e-commerce sites that often cannot enforce their policies against fraud.

Now there are hundreds of tools designed to recreate someone's image and voice, said Vijay Balasubramaniyan, CEO of Pintroop, a company that keeps trace of the deceptive uses of AI technology has become so sophisticated that Swindlers can create convincing implements from a few clips or photos.

“I can actually create a Bot Ai who resembles you and have full -blown conversations of your LinkedIn profile,” he said.

Dr. Gemma Newman, a family doctor in Great Britain and author of two books on Nutrition and Health, went to Instagram in April to warn her followers on a video on Tiktok who had been changed to make it seem that he was promoting capsules of vitamin B12 and 9,000 milligrams of “pure nutrients rich in nutrients”.

Dr. Newman was horrified: his similarity was to push a supplement, which could be harmful to high doses, playing on women's insecurities – which implies that the pills could make them “feel desirable, admired and safe”.

The video was so realistic that her mother believed it was her.

“It's a double betrayal because my image is there, supporting something I don't think,” he said.

The impersonation of medical professionals extends beyond the unremely demonstrated supplements.

Dr. Eric Topol, cardiologist and founder of the Scrips Research Translational Institute of San Diego, discovered that there were dozens of apparent spin -ff Ai of his new book on Amazon. One of his patients unconsciously purchased a false memorial, complete with a portrait generated by the AI of Dr. Topol on the cover.

Christopher Gardner, a Stanford nutritional scientist, recently found the unconscious face of at least six YouTube channels, including one called “Nutrient Nerd”.

Together, the channels have hundreds of videos, many narrated by a version generated by the voice of Dr. Gardner. Most videos targe the elderly and make advice that does not approve, facing problems such as pain in arthritis and muscle loss. Impersonations like these could be an effort to build quite large followers on the platform for qualifying for programs to earn a share of advertising revenues.

The dissemination of these fakes has made standard advice on how to find good information on online health suddenly, said Dr. Eleonora Tiplinsky, an oncologist who found impostors on Facebook, Instagram and Tiktok.

“This undermines all the things that we tell people about how to identify online disinformation: are they real people? Do they have a hospital page?” he said. “How would people know that it's not me?”

In an interview, Dr. Gardner said he was worried about the amount of online nutritional disinformation. He was active on social media and appeared on podcasts to make the record clear, he said.

Now, Dr. Gardner wonders if those efforts have twisted against him, providing a library of recordings that can be used to impersonate it. Experiences such as his May discourage other experts from adventing in online conversations, he said. “So the credible voices will be drowned even more.”

Dr. Gardner and a representative of Stanford spent hours reporting videos to YouTube and federal authorities. They also published comments on the videos that warn that the videos were falsely impersonating Dr. Gardner, but most of these comments were eliminated in a minute.

A YouTube spokesman, Jack Malon, told the New York Times that the platform had removed “several channels” for violating his policies against spam. Tiktok said in a statement that did not allow most of the imitations but did not face Dr. Newman's video.

Other doctors, not having had luck in reporting the impostors, turned to more desperate streets to get the pages.

After repeated relationships and a threat of a legal threat were apparently ignored by Meta, Dr. Tiffany Troso-Sandoval, an oncologist who manages educational pages focused on women's tumors, paid about $ 260 to someone on Fiverr, the online market for small services, which promised to obtain a Facebook page of impostor. It didn't work.

The supplement brand that impersonated Dr. Lustig on Facebook has also created false posts in numerous other countries, including those with real doctors in Australia and Ireland.

The geographical range has shown that it was the type of great and sophisticated operation that is becoming more and more a threat to brands all over the world, said Yoav Keren, CEO of Brandshied, a computer security company in Israel who discovered it.

The campaign, which seemed to start at the end of last year, was exploiting the popularity of a class of drugs known as GLP-1, which transformed the treatment of diabetes, obesity and related diseases. He launched a product called Peaka, which seemed to be liquid capsules. (The only approved forms of the GLP-1 now available are injections.)

Qui-Today-Tomorrow websites with Hong Kong recordings are sold here, Keren said, but those who are exactly behind them remain unknown.

Despite its uncertain origin and false marketing, the product was until recently for the purchase on the main e-commerce platforms, including Amazon and Walmart, and appeared in research on Google as a sponsored product. (Amazon began to remove it after being contacted by the Times. Walmart said that the product was not sold in its stores, but the third-party sellers, in violation of the retailer's policies, were selling the product on its e-commerce site; since then those sellers have been removed.)

In addition to impersonating the doctors, the marketing campaign presented logos of regulatory agencies or defense groups in different countries, including Mexico, Norway, Great Britain, Canada and New Zealand, falsely implying the product received the official approval, according to Brandshield. In the United States, groups included the Obesity Society, whose website now has a pop-up warning on what he called an “e-commerce scam”.

Dr. Caroline Apovian, co-director of the For Weight Management and Wellness Center at the Brighham and Women's Hospital and Professor at the Harvard Medical School, learned that she had become an unaware Huckster for Peaka when patients started sending messages and emails to ask for what seemed to be “his approval” on Facebook.

Dr. Apovian and her colleagues in the end found 20 accounts that impersonate her, the posts and announcements have set together with authentic details and real photographs on her Facebook and LinkedIn accounts. He defined the “insidious and dangerous” campaign.

The same Facebook users raised doubts about the product in the comments that respond to false posts or in groups dedicated to weight loss. Some warn that it was not what he claimed to be. A woman who bought her asked the Falor Doctor Apovian advice on dosage because it was not clear from the package.

Cam Carter, who lives outside Victoria in Australia, said that Peaka said he was made in Australia, but the three boxes he purchased for about $ 45 (70 Australian dollars) arrived from China. It was also overloaded by Paypal and had to climb to obtain only a partial refund.

“He does nothing as advertised,” he wrote in response to questions about his experience.

Meta, the company owner of Facebook, prohibits imitations on its platforms, but indicated that it was not aware of the fake accounts until the Times contacted it. Last week, he began to remove those of several doctors involved, said the company.

“We know that there will be examples of things that we could lose,” said the company in a declaration noting that he was launching new efforts to detect diving of public figures or celebrities.

Dr. Michael Horowitz, an important researcher of gastroenterology at the University of Adelaide and the Royal Adelaide Hospital in Australia, said that the fraud prey on people who had fought throughout their lives with weight loss or diabetes and that they may not be able to afford the approved GLP-1 medicines.

“They are identifying vulnerable, knowing that what they are offering is nothing,” he said. “So I consider it a reprovinous behavior.”