Scientists are proposing a new way of understanding the genetics of Alzheimer's that would mean up to a fifth of patients would be considered to have a genetically caused form of the disease.

Currently, the vast majority of Alzheimer's cases do not have a clearly identified cause. The new designation, proposed in a study published Monday, could broaden the scope of efforts to develop treatments, including gene therapy, and influence the design of clinical trials.

It could also mean that hundreds of thousands of people in the United States alone could, if they wanted, receive a diagnosis of Alzheimer's before developing any symptoms of cognitive decline, even though there are currently no treatments for people at that stage.

The new classification would make this type of Alzheimer's one of the most common genetic diseases in the world, medical experts said.

“This reconceptualization that we propose concerns not a small minority of people,” said Dr. Juan Fortea, author of the study and director of the Sant Pau Memory Unit in Barcelona, Spain. “We sometimes say we don't know the cause of Alzheimer's disease,” but, he said, that would mean that about 15 to 20 percent of cases “can be traced back to a cause, and the cause is in the genes.” “

The idea involves a genetic variant called APOE4. Scientists have long known that inheriting one copy of the variant increases the risk of developing Alzheimer's, and that people with two copies, inherited from each parent, have a significantly increased risk.

The new study, published in the journal Nature Medicine, analyzed data from more than 500 people with two copies of APOE4, a significantly larger pool than previous studies. The researchers found that nearly all of these patients developed the biological pathology of Alzheimer's, and the authors say that two copies of APOE4 should now be considered a cause of Alzheimer's, not simply a risk factor.

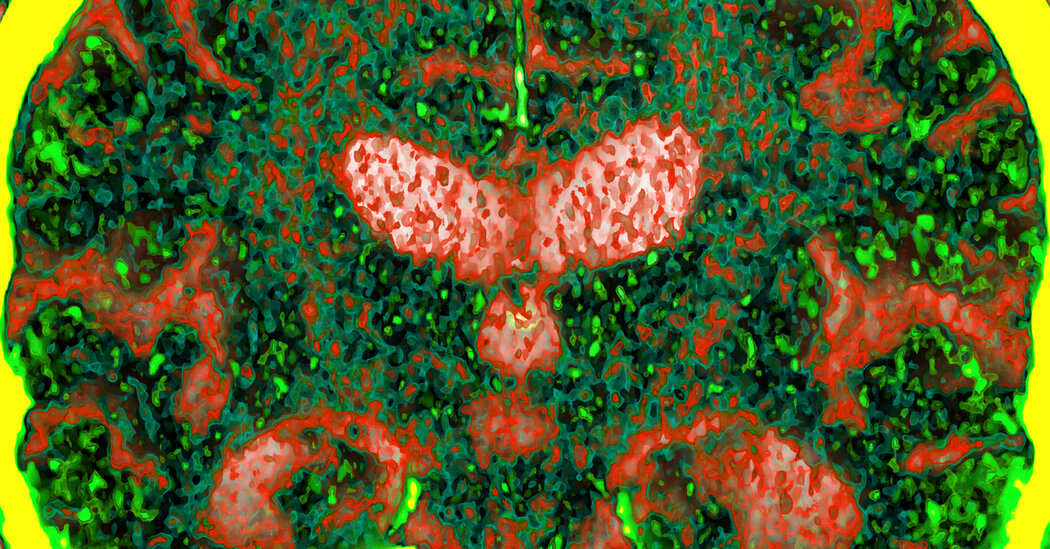

The study found that patients developed Alzheimer's pathology even at a relatively young age. By age 55, more than 95% had biological markers associated with the disease. By age 65, almost everyone had abnormal levels of a protein called amyloid that forms plaques in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer's. And many began developing symptoms of cognitive decline at age 65, younger than most people without the APOE4 variant.

“The key thing is that these individuals are often symptomatic 10 years earlier than other forms of Alzheimer's disease,” said Dr. Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at Mass General Brigham in Boston and an author of the study.

He added: “When they are caught and diagnosed clinically, because they are often younger, they have more pathology.”

People with two copies, known as APOE4 homozygotes, make up 2 to 3 percent of the general population, but are estimated to account for 15 to 20 percent of people with Alzheimer's dementia, experts said. People with one copy make up about 15-25% of the general population and about 50% of Alzheimer's dementia patients.

The most common variant is called APOE3, which appears to have a neutral effect on Alzheimer's risk. About 75% of the general population has one copy of APOE3, and more than half of the general population has two copies.

Alzheimer's experts not involved in the study said that classifying the two-copy condition as genetically determined Alzheimer's could have significant implications, including encouraging drug development beyond the industry's recent major focus on treatments that target and reduce amyloid .

Dr. Samuel Gandy, an Alzheimer's researcher at Mount Sinai in New York who was not involved in the study, said patients with two copies of APOE4 face much higher safety risks from anti-amyloid drugs.

When the Food and Drug Administration approved the anti-amyloid drug Leqembi last year, it required a black box warning on the label that said the drug can cause “serious, life-threatening events” such as swelling and bleeding in the brain, particularly for people with two copies of APOE4. Some treatment centers have decided not to offer these patients Leqembi, an intravenous infusion.

Dr. Gandy and other experts said that classifying these patients as having a distinct genetic form of Alzheimer's would galvanize interest in developing safe and effective drugs for them and add urgency to current efforts to prevent cognitive decline in people who do not still have symptoms. .

“Rather than say we don't have anything for you, let's look for a study,” Dr. Gandy said, adding that such patients should be included in studies at younger ages, given how early their pathology begins.

In addition to trying to develop drugs, some researchers are exploring gene editing to turn APOE4 into a variant called APOE2, which appears to protect against Alzheimer's. Another gene therapy approach being studied involves injecting APOE2 into patients' brains.

The new study had some limitations, including a lack of diversity that could have made the findings less generalizable. Most of the patients in the study had European ancestry. Although two copies of APOE4 greatly increase Alzheimer's risk in other ethnicities, the risk levels differ, said Dr. Michael Greicius, a neurologist at Stanford University School of Medicine who was not involved in the research.

“An important argument against their interpretation is that the risk of Alzheimer's disease in APOE4 homozygotes varies substantially between different genetic ancestors,” said Dr. Greicius, co-author of a study that found that whites with two copies of APOE4 had 13 times the risk of whites with two copies of APOE3, while blacks with two copies of APOE4 had a 6.5 times greater risk than blacks with two copies of APOE3.

“This has critical implications when counseling patients about their genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease, based on their ancestry,” he said, “and also speaks to some yet-to-be-discovered genetic and biological aspects that presumably drive this huge difference in risk”.

According to current genetic knowledge of Alzheimer's, fewer than 2% of cases are considered genetically caused. Some of these patients have inherited a mutation in one of the three genes and may develop symptoms as early as their 30s or 40s. Others are people with Down syndrome, who have three copies of a chromosome containing a protein that often leads to what is called Alzheimer's disease associated with Down syndrome.

Dr. Sperling said that genetic alterations in these cases are thought to fuel amyloid buildup, while APOE4 is thought to interfere with the clearance of amyloid buildup.

Under the researchers' proposal, having one copy of APOE4 would continue to be considered a risk factor, not enough to cause Alzheimer's, Dr. Fortea said. It's unusual for diseases to follow that genetic pattern, called “semi-dominance,” with two copies of a variant causing the disease, but one copy only increasing the risk, experts said.

The new recommendation will raise questions about whether people should get tested to determine if they have the APOE4 variant.

Dr. Greicius said that until there are treatments for people with two copies of APOE4 or trials of therapies to prevent them from developing dementia, “My recommendation is that if you have no symptoms, you should definitely not understand your condition APOE”.

He added: “It will only cause pain at this point.”

Finding ways to help these patients can't come soon enough, Dr. Sperling said, adding, “These individuals are desperate, they've seen this a lot in both of their parents, and they really need therapies.”