An independent advisory panel to the Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday rejected the use of MDMA-assisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, highlighting the unprecedented regulatory challenges of a new therapy using the drug commonly known as Ecstasy.

Before the vote, committee members expressed concerns about the design of the two studies submitted by the drug's sponsor, Lykos Therapeutics. Many questions focused on whether study participants were generally able to correctly guess whether they had taken MDMA, also known as Ecstasy or Molly.

The jury voted 9-2 on the effectiveness of MDMA-assisted therapy and 10-1 on whether the benefits of the proposed treatment outweighed the risks.

Other speakers expressed concerns about the drug's potential cardiovascular effects and possible biases among the therapists and facilitators who led the sessions and which may have positively influenced patient outcomes. A case of misconduct involving a patient and a therapist in the study also weighed on some panelists' minds.

Many committee members said they were particularly concerned about Lykos' failure to collect detailed data from participants about the potential abuse of a drug that generates feelings of bliss and well-being.

“I absolutely agree that we need new and better treatments for PTSD,” said Paul Holtzheimer, deputy director of research at the National Center for PTSD, a speaker who voted no on the question of whether the benefits of MDMA therapy outweighed the risks.

“However, I also note that premature introduction of a treatment can actually stifle development, stifle implementation, and lead to premature adoption of treatments that are not fully known to be safe, not fully effective, or not used with their optimal efficacy,” he said. added.

While the vote is not binding on the FDA, the agency often follows the recommendations of its advisory panels. The agency's final decision is expected in mid-August.

MDMA, or methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also sometimes called midomaphetamine, is a synthetic psychoactive drug that promotes self-awareness, feelings of empathy, and social connection.

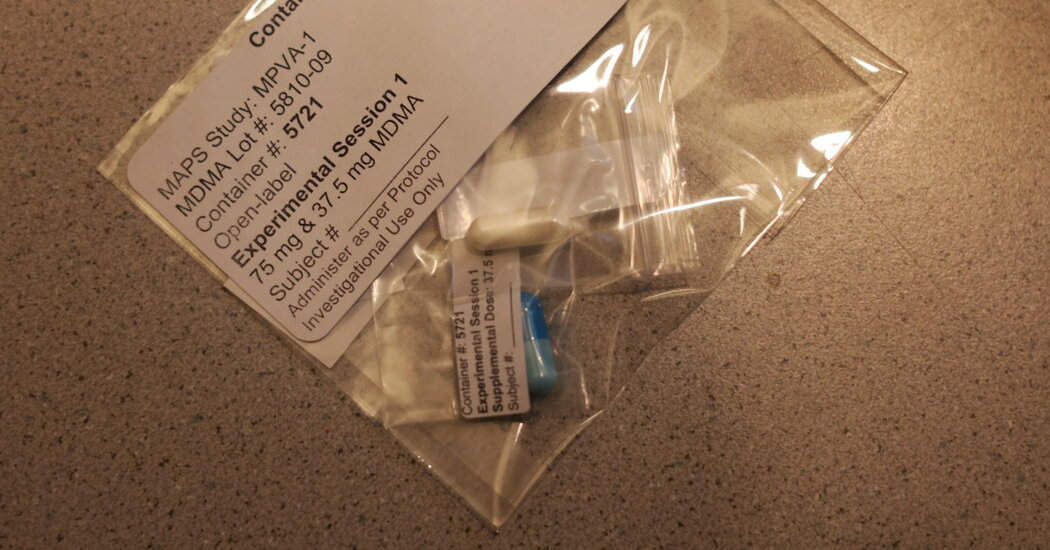

The illegal drug is listed as a Schedule I substance, defined as having no accepted medical use and having a high potential for abuse. If it were to gain FDA approval, federal health authorities and Justice Department officials would have to follow certain steps to downgrade the drug's list, much like the process currently underway with cannabis.

The DEA could also set manufacturing quotas for drug ingredients, as it does with stimulant drugs used to treat ADHD.

With the panel's focus on topics like “euphoria,” “suicidal ideation” and “expectation bias,” Tuesday's one-day session demonstrated the nuances and complexities facing regulators as they grapple with land unknown of a therapy that has only recently entered traditional psychiatry. after the decades-long national war on drugs.

An additional problem: the FDA is a drug regulator. It does not regulate psychotherapy and has not evaluated drugs whose effectiveness is linked to talk therapy.

If approved, MDMA-assisted therapy would be the first new treatment for PTSD in nearly 25 years. The condition, which affects about 13 million Americans, has been implicated in the huge suicide rate among military veterans, whose suffering has galvanized lawmakers of both parties and prompted a sea change in public attitudes toward treatment based on psychedelic compounds.

According to studies presented by Lykos, patients who received MDMA plus psychotherapy reported significant improvements in their mental health. The most recent study on the drug found that more than 86 percent of those who took MDMA achieved a measurable reduction in the severity of PTSD symptoms.

About 71% of participants improved enough to no longer meet the criteria for a diagnosis. According to the data presented, among those who took the placebo, 69% improved and almost 48% no longer qualify for a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

The questions, concerns and evident skepticism expressed by the 10-member panel echoed those raised by agency staff members, who last week released a briefing paper aimed at helping the panel evaluate the effectiveness and potential adverse health effects of MDMA therapy.

In her opening remarks, Dr. Tiffany Farchione, director of the FDA's Division of Psychiatry, highlighted the regulatory challenges posed by MDMA, saying that “we've been learning as we go.” But in her testimony and in staff documents, she and other agency officials repeatedly noted that the study's overall findings were significant and long-lasting.

“Although the application presents a number of complex review issues, it includes two positive studies in which participants in the midomafetamine arm experienced statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in their PTSD symptoms,” he said. “And that improvement appears to be lasting for at least several months after the end of the acute treatment period.”

Much of the criticism of Lykos' study designs has focused on so-called functional unraveling, a problem that plagues many studies involving psychoactive compounds. Although the approximately 400 patients who took part in the studies were not told whether they had received MDMA or a placebo, to reduce the chance of bias in the results, the vast majority were acutely aware of any altered mental state, leading them to correctly guess which study arm they were enrolled in.

The FDA, which worked with Lykos to design the trials, has acknowledged shortcomings in study design and recently issued new guidelines to address issues facing psychedelic researchers.

Numerous other critical voices have emerged in recent months. Among them is the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a nonprofit that examines the costs and effectiveness of drugs, which released a report calling the effects of the treatment “inconclusive” and questioning the results of Lykos' study.

Other organizations, such as the American Psychiatric Association, did not openly oppose approval, but called on the FDA to mitigate any negative consequences by developing strong regulations, rigorous controls on prescribing and dispensing, and careful monitoring of patients.

FDA staff analysis recommended that approval be contingent on limited health conditions, patient monitoring, and diligent reporting of adverse events.

Shortly before Tuesday's vote, the advisory committee heard from more than 30 speakers who expressed sharply divergent views on the application.

Several critics have focused on Rick Doblin, a veteran psychedelic advocate who in 1986 founded the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, the nonprofit organization that submitted the original application for MDMA-assisted therapy to the FDA. The organization later created a for-profit entity that became Lykos earlier this year.

Brian Pace, a professor at Ohio State University, described the company seeking approval as a “therapeutic cult” and criticized Mr. Doblin's public comments highlighting his zeal for psychedelics, including the belief that legalizing them and regulating them would have brought peace to the world.

But most of those who spoke in favor of the application offered deeply personal accounts of how MDMA therapy had largely calmed the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Among them was Cristina Pearse, who said she suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after being sexually assaulted when she was 9 years old. Over the years, she said she had been prescribed a litany of psychiatric medications and at one point she attempted suicide.

MDMA therapy, she said, changed her life. “What once felt like a tsunami of overwhelming panic was now simply a puddle at my feet,” said Ms. Pearse, who founded an organization that helps women recover from trauma.

He concluded his testimony by urging the FDA to approve the application.

“How many more people have to die before an effective therapy is approved?” she asked. “As you evaluate your risk, keep in mind that this therapy can save many lives. I have lost much of my life to this disease. I'm grateful to get it back now. But I wish this was a drug approved decades ago.”