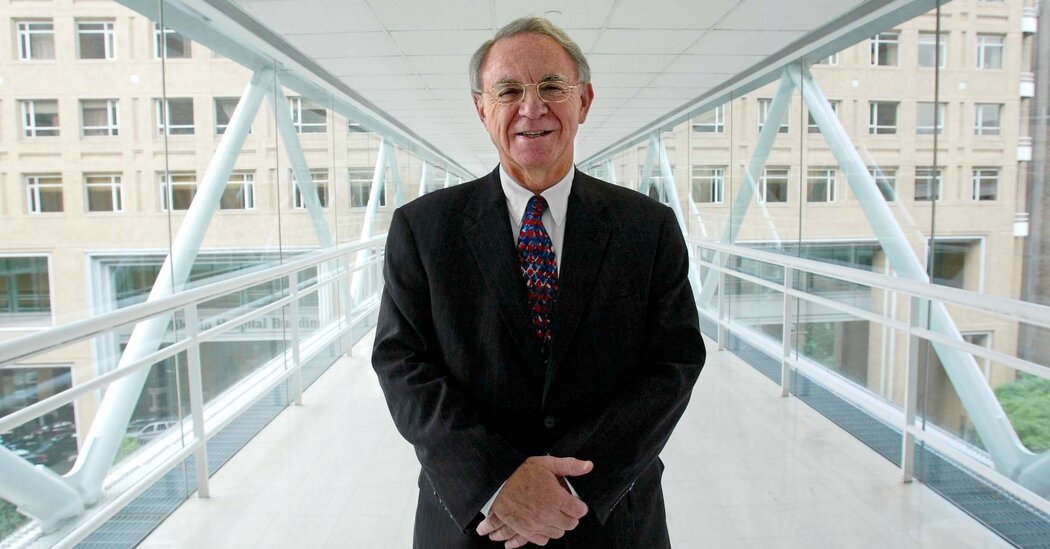

Dr. Herbert Pardes, a psychiatrist and former director of the National Institute of Mental Health who led the merger of two major medical centers that became New York-Presbyterian Hospital and ran it for 11 years, died April 30 at his home in Manhattan . He was 89 years old.

His son Steve said the cause was aortic stenosis.

Dr. Pardes (pronounced par-diss) was named president and CEO of the hospital in late 1999, nearly two years after the merger of New York Hospital and Presbyterian Hospital. For the previous decade he had been dean of the medical school at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons, Presbyterian's affiliated medical school.

“It was no secret that as dean of the medical school I didn't always agree with hospital administration,” he said in his thick Bronx accent on CUNY TV in 2011. “I thought maybe I could create a better collaboration examining to manage the hospital”.

The merger created one of the largest healthcare institutions in the country, with 2,369 hospital beds, 13,000 employees and $1.6 billion in annual revenue. With 167 facilities, it extends from Manhattan to Rockland and Orange counties in New York. Its hospitals include Weill Cornell Medical Center in Manhattan.

“It was a surprisingly successful merger considering the different cultures of the two institutions,” Kenneth E. Raske, president of the Greater New York Hospital Association, a trade group, said in an interview. “It was the bridge that enabled the smooth, wrinkle-free transition of that institution.”

But Alan Sager, a professor of health law at Boston University, without commenting on the New York-Presbyterian merger, said in an email: “Merger supporters always say, in a self-sanctifying way, that they are merging to help us, not themselves. But if mergers reduced costs (never proven), larger hospital surpluses would result, not a reduction in insurance premiums.”

Dr. Pardes aspired to make New York-Presbyterian a model for medical care, with intense attention to patients, efficient management, and tight financial controls. He visited beds, insisted that nurses memorize the names of patients and their families, and ordered that rooms and entrances be painted in soothing colors.

“I've never been able to overcome a problem,” he said in a New York Times profile of him in 2007. “I have to solve it. This profession is first and foremost about helping patients survive: it always has been. Unfortunately, I think we can sometimes lose sight of that.

Mr. Raske said: “Weed approached life's problems with a childlike smile and a touch of borscht humor.”

Dr. Pardes was a prodigious fundraiser for New York-Presbyterian, helping secure donations from the mega-rich to build facilities such as the Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital, the Vivian and Seymour Milstein Family Heart Center, and men's health centers and female Iris Cantor. , all in Manhattan.

“He had a way of socializing with people of great power and convincing them to give great gifts,” Steve Pardes said.

Herbert Pardes was born on July 7, 1934 in the Bronx and grew up primarily in Lakewood, NJ. His parents, Louis and Frances (Bergman) Pardes, owned the Hotel Greenwood in Lakewood, which was converted into a nursing home in the late 1950s and operated resorts in the Catskills' borscht belt.

At age 7, Herbert was diagnosed with Perthes disease, a rare childhood disease in which the blood supply to the ball and socket joint of the hip joint is temporarily cut off, weakening the bone. Although he recovered without any permanent damage, he spent 10 months hospitalized with his body in a full cast. Gloomy doctors stuck needles in him without explanation, and hospital rules limited his parents' visits to just an hour a few times a week, he recalled. The experience traumatized him but, decades later, helped motivate him to be more attentive to patients.

As a young man he worked for his parents, watching how they pampered the resort's guests. He sold drinks for 10 cents, raised money for the war effort, was a bellboy, waited tables and became maître d'hôtel.

“The dining room was a microcosm of eccentric behavior, a great behavioral laboratory for someone who would become a psychiatrist,” Dr. Pardes told the Times in 2003.

He graduated from Rutgers University in 1956, then earned his medical degree in 1960 from SUNY Downstate College of Medicine (now SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University) in Brooklyn. He did his medical internship and psychiatric residency at Kings County County Hospital in Brooklyn from 1960 to 1962.

After being drafted into the Army, Dr. Pardes ran the mental health clinic at Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia, from 1962 to 1964. He was discharged and completed his residency in 1966, then graduated from the New York Psychoanalytic Institute in 1970.

For much of the next two decades he built his career around mental health as chair of the Downstate Department of Psychiatry, chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Colorado Medical Center in Denver, and director of the NIMH, where he strengthened his research. plan.

In 1984, Dr. Pardes was appointed director of the psychiatry service at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and chair of the department of psychiatry at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. Five years later, he was named vice president of the College of Health Sciences and dean of the medical school, allowing him to lead New York-Presbyterian Hospital after the merger.

In addition to his son Steve, he leaves behind two other sons, James and Lawrence, six grandchildren, and his partner, Dr. Nancy Wexler, a professor of neuropsychology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons who was the principal investigator for a two-decade study Huntington's disease in an extended family in Venezuela. She herself has the disease. He had been separated from his wife, Judith (Silber) Pardes, since the 1980s. She died in 2022.

Dr. Pardes was a well-paid nonprofit executive, even after stepping down as president and CEO in 2011. He was later named executive vice president of the hospital's board of trustees, a position that compensation experts said was rare in the non-profit world. , according to a Times article in 2014.

In 2011, his last year leading the hospital, he earned $4.1 million (equivalent to about $5.8 million today). Then, as executive vice president, he received $5.5 million, including $2 million in deferred compensation in 2012. Through 2022, he received at least $2 million per year.

Frank Bennack Jr., then chairman of the hospital's board, told the Times in a statement in 2014 that Dr. Pardes had been hired for “urgent fundraising activities and a variety of other institutional needs with which he could assist the his superb successor”.

Dr. Steven J. Corwin succeeded him and remains in that position.

Steve Pardes said the focus on compensation bothered his father. “When he compared himself to CEOs of profitable companies, he may have been undercompensated,” Pardes said. “But he wasn't focused on money. He wanted to be paid a fair wage for what he had contributed.”