When the letter arrived in Westil Gonzalez’s prison cell saying he had been granted parole, he couldn’t read it. Over the 33 years he had been locked up for murder, multiple sclerosis had taken away much of his sight and left him wheelchair-dependent.

He had a clear idea of what he would do once he was freed. “I want to give my testimony to a couple of young people who are out there, collecting guns,” Mr. Gonzalez, 57, said in a recent interview. “I want to save one person from what I went through.”

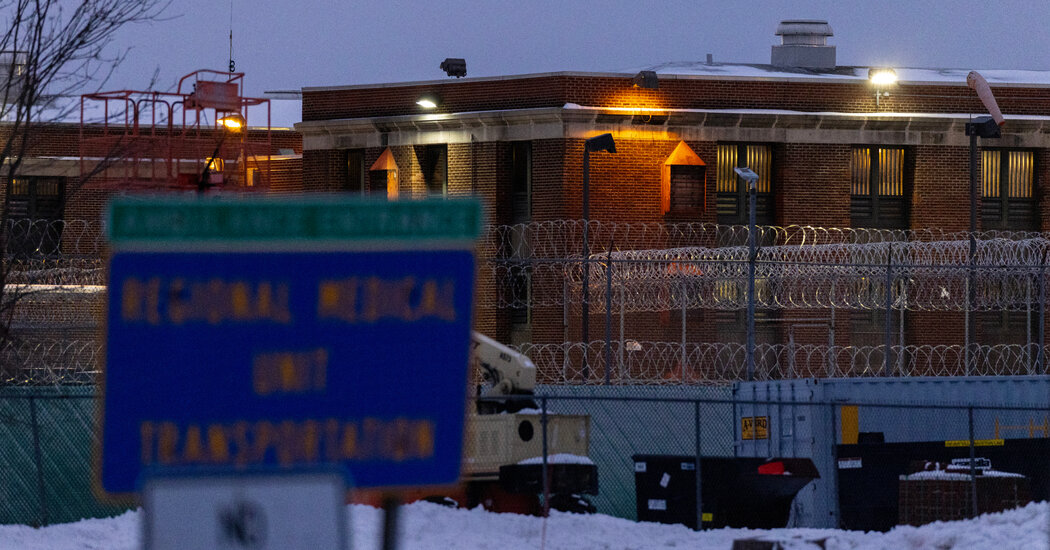

But six months have passed and Mr. Gonzalez is still incarcerated outside Buffalo because the Department of Corrections has not found a halfway house that will accept him. Another New York inmate has been in the same limbo for 20 months. Others were released only after suing the state.

America’s elderly prison population is growing, in part due to the growing number of people serving long sentences for violent crimes. Nearly 16% of inmates were older than 55 in 2022, up from 5% in 2007. The percentage of inmates older than 65 quadrupled over the same period, reaching about 4%.

Complex and expensive medical conditions require increased nursing care, both in prison and after the inmate’s release. Across the country, prison systems attempting to discharge inmates convicted of serious crimes often find themselves with few options. Nursing home beds can be difficult to find even for those without criminal records.

Spending on inmate medical care is on the rise: In New York it grew to just over $7,500 in 2021 from about $6,000 per capita in 2012. Even so, those who work with inmates say the money often doesn’t are enough to keep up with the growing percentage of older inmates who have chronic health problems.

“We see a lot of unfortunate gaps in health care,” said Dr. William Weber, an emergency physician in Chicago and medical director of the Medical Justice Alliance, a nonprofit that trains doctors to work as expert witnesses in cases that involve prisoners. With inmates often having trouble getting specialist care or even copies of their medical records, “things fall by the wayside,” he said.

Dr. Weber said he had recently been involved in two cases of seriously ill prisoners, one in Pennsylvania and the other in Illinois, who could not be released without admission to a nursing home. The Pennsylvania inmate died in prison and the Illinois man remains incarcerated, he said.

Nearly all states have programs that allow for the early release of inmates with serious or life-threatening medical conditions. New York’s program is one of the most extensive: While other states often limit the policy to those with less than six months to live, New York’s is open to anyone with a terminal or debilitating illness. Nearly 90 people were granted medical parole in New York between 2020 and 2023.

But the occupancy rate of state nursing homes hovers around 90%, one of the highest in the nation, making it especially difficult to find places for prisoners.

The prison system is “competing with hospital patients, rehabilitation patients and the general public who need trained nurses for the limited number of available beds,” said Thomas Mailey, a spokesman for the New York City Department of Corrections and Community Supervision. He declined to comment on Mr. Gonzalez’s case or the medical conditions of any other inmates.

Persons on probation remain in state custody until their original prison term expires. Courts have previously upheld the state’s right to place conditions on prisoner releases to safeguard the public, such as preventing paroled sex offenders from living near schools.

But lawyers and medical ethicists argue that patients on probation should be allowed to choose how they receive their care. And some have noted that these prisoners’ medical needs are not necessarily met in prison. Mr. Gonzalez, for example, said he had not received glasses, despite repeated requests. His illness caused one of his hands to curve inward, leaving uncut nails digging into his palm.

“While I understand the difficulty of finding placements, the default solution cannot be continued incarceration,” said Steven Zeidman, director of the criminal defense clinic at the CUNY School of Law. In 2019, one of his clients died in prison weeks after being granted medical parole.

New York does not publish data on how many inmates are awaiting placement in nursing homes. A 2018 study found that, between 2013 and 2015, six of 36 inmates granted medical parole died before a placement was found. The medical parole process unfolds slowly, the study showed, and it sometimes takes years for a prisoner to get an interview about his possible release.

Finding a nursing home can prove difficult even for a patient without a criminal record. Facilities have struggled to recruit staff, especially after the coronavirus pandemic. Nursing homes may also worry about the safety risk of someone with a prior conviction or the financial risk of losing residents who don’t want to live in a facility that accepts ex-offenders.

“Nursing homes have concerns, and whether they’re rational or not, it’s pretty easy to not answer or not return that phone call,” said Ruth Finkelstein, a Hunter College professor who specializes in senior policy and has reviewed legal documents at Hunter College. The Times’ request.

Some people involved in these cases have said that New York prisons often perform little more than a cursory search for nursing care.

Jose Saldana, director of a nonprofit called Release Aging People in Prison Campaign, said that when he was incarcerated at the Sullivan Correctional Facility from 2010 to 2016, he worked in a department that helped coordinate inmate releases on probation. He said he often reminded his supervisor to call nursing homes that didn’t respond the first time.

“They would say they have too many other responsibilities to stay on the phone,” Saldana said.

Mr. Mailey, a spokesman for the New York Department of Corrections, said the agency had multiple discharge teams looking for placement options.

In 2023, Arthur Green, a 73-year-old kidney dialysis patient, sued the state for release four months after being granted medical parole. In his lawsuit, Mr. Green’s lawyers said they had secured him a stay in a nursing home, but that it had lapsed because the Department of Corrections had submitted an incomplete application to a nearby dialysis center.

The state found placement for Mr. Green a year after his parole date, according to Martha Rayner, a lawyer who specializes in prisoner release cases.

John Teixeira was granted medical parole in 2020, at age 56, but remained incarcerated for two and a half years while the state searched for a halfway house. He had a history of heart attacks and was taking daily medications, including one administered through an intravenous route. But an assessment by an independent cardiologist concluded that Mr Teixeira did not require nursing care.

Lawyers for the Legal Aid Society of New York sued the state for his release, pointing out that while he waited, his port became repeatedly infected and his diagnosis went from “advanced” heart failure to “stage terminal”.

The Department of Corrections responded that 16 nursing homes had refused to accept Mr. Teixeira because they could not handle his medical needs. The case was resolved three months after the suit was filed, when “the judge put considerable pressure” on the state to find a suitable location, according to Stefen Short, one of Mr. Teixeira’s lawyers.

Some sick prisoners awaiting release had difficulty receiving medical care inside.

Steve Coleman, 67, has difficulty walking and spends much of his day sitting. After 43 years in prison for murder, he was granted parole in April 2023 and remains in prison while the state searches for a nursing home that can coordinate with a three-times-weekly kidney dialysis center.

But Mr. Coleman has not had dialysis treatment since March, when the state contracted with his provider. The prison offered to take Mr Coleman to a nearby clinic for treatment, but he refused because he found the transport protocol – which involves a search and the use of shackles – painful and invasive.

“They say you have to do a search,” he said in a recent interview. “If I’m on parole, I can’t walk, and I go to the hospital, who could I hurt?”

Volunteers from the nonprofit Parole Prep Project, which assisted Mr. Coleman with his parole application, received a letter from Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City in June offering to provide him with medical care and help him reintegrate into the community.

Still incarcerated two months later, Mr. Coleman sued for his release.

In court filings, the State argued that it would be “dangerous and irresponsible” to release Mr. Coleman without a plan to address his medical needs. The state also said it contacted Mount Sinai, as well as hundreds of nursing homes, about Mr. Coleman’s placement and never heard back.

In October, a court ruled in favor of the prison system. Describing Mr. Coleman’s situation as “very sad and frustrating,” Justice Debra Givens of the New York State Supreme Court concluded that the state had a rational reason to hold Mr. Coleman beyond his parole date. Ms. Rayner, Mr. Coleman’s lawyer, and the New York Civil Liberties Union appealed the ruling on Wednesday.

Fourteen medical ethicists sent a letter to the prison advocating Mr. Coleman’s release. “Forcing continued detention under the guise of ‘best interests,’ even if doing so with good intentions, violates his autonomy,” they wrote.

Several other states have come up with a different solution for people on parole: soliciting the business of nursing homes that specialize in housing patients rejected elsewhere.

A private company called iCare opened the first such facility in Connecticut in 2013, which now houses 95 residents. The company operates similar nursing homes in Vermont and Massachusetts.

David Skoczulek, iCare’s vice president of business development, said these facilities tend to save states money because the federal government covers some of the costs through Medicaid.

“It is more humane, less restrictive and cost-effective,” he said. “There is no reason for these people to remain in a penitentiary environment.”